An essay by Desmond Ashmore, as provided by James Hanson

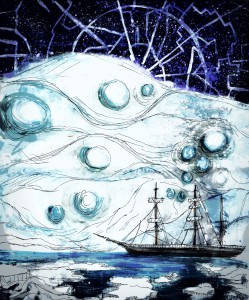

Art by Luke Spooner

May 25th, 1863

I have been vindicated by my machine, which was unfortunately audible for the better part of three days and required constant attendance. My groundskeeper and I alternated in two hour shifts of stoking the machine’s fire and replenishing its oil when necessary. If the torque from the pistons drops too low, some of the more delicate gears can seize up and crack, ruining both the calculation and the machine itself. There is a governor that is intended to halt the operation of the machine before this happens, but it is unwise to trust it, since the better part of the engineering in this machine has gone into its primary function.

After two nights of strong coffee and bleary eyes, the machine’s bell rang once, which I always include at the end of my programmes, and there was a stack of newly punched data cards sitting in the output tray.

I transcribed the data and my mounting suspicion was confirmed. It is so preposterous to even entertain the idea that I have been afraid to record it anywhere, but now I have a calculation, which will of course have to be reconfirmed, which lends credence to this incredible idea that has entered my head uninvited and has been incubating there like a botfly maggot. I am now finally sure enough to commit it to writing. I now believe that

⁂

I turned the page. The back of that page was a jumble of figures and calculations. The most prominent constant I found in Baxendell’s notes was his poor grasp of demarcation. Random thoughts and ideas peppered the borders of nearly everything he wrote, and his notebooks’ labels meant very little by the tenth or twentieth page.

The next page was missing. It was torn out as neatly as possible. I had not noticed this before. A survey of the rest of the volume turned up a few more missing pages. There was clear intent in the pattern of omission. I assumed that the only person who could have done it was Baxendell himself. Perhaps he had realised that his idea was flawed and, out of embarrassment, destroyed the incriminating writings. The problem with that was that I saw no evidence of this realisation in his notes.

This piqued my curiosity enough for me to get up and walk back to the ship. We already had all of the supplies we would need, but now I decided I wanted to bring one more thing. I ascended the pilot ladder, grabbed an oil lamp, and, taking a deep breath, descended below deck to the ship’s library, which was remarkably well stocked for a sailing ship, but not for a polar ship. It had been discovered long ago that boredom was as much an enemy as scurvy when wintering in a polar climate. I found the ship’s copy of Euclid’s Elements and hastily returned to the pallid light outside.

And yet beyond the end of the stars, at the perfect centre of the everted heavens, was something I have no words for. It was featureless and yet I knew that it looked back at me through that lens. I had to pull myself out. Why had God created us if we were but microscopic bacteria on the inner edge of–what? An egg? A prison?

To read the rest of this story, check out the Mad Scientist Journal: Summer 2014 collection.

Desmond Ashmore is an astronomer and fellow at the University of Cambridge. He is best known for making spectroscopic observations in India during the eclipse of 1868 which lead to the discovery of the hitherto unknown element Solium, which comprises the atmosphere of the Sun.

James Hanson is a physics graduate student at the University of Wisconsin-Madison. He often finds himself torn between his love of cerebral hard science fiction and his fondness for bad 50s-era special effects. This is his first publication since high school.

Luke Spooner a.k.a. ‘Carrion House’ currently lives and works in the South of England. Having recently graduated from the University of Portsmouth with a first class degree he is now a full time illustrator for just about any project that piques his interest. Despite regular forays into children’s books and fairy tales his true love lies in anything macabre, melancholy or dark in nature and essence. He believes that the job of putting someone else’s words into a visual form, to accompany and support their text, is a massive responsibility as well as being something he truly treasures. You can visit his web site at www.carrionhouse.com.

Follow us online: