An essay by Luisa Sontag, as provided by George Salis

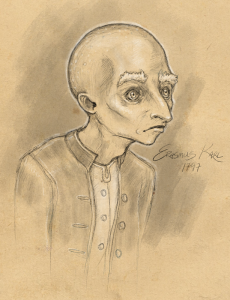

Art by Leigh Legler

“If thy heart were a nest, thou would begat many birds.” –The Purloined Philosophia by Boris of Aventaria

There has been much controversy, even mythology, surrounding the so-called “nidificant manuscript.” A few notables, including the biolinguist Norman Mast, have clamored to call it “an anachronistic masterpiece of scientific literature” (34), suggesting it has been passed down to us from the future, or an alternate past. Many others have deemed the work “a hoax of adolescent caliber” (Mare 25). But by studying the work and delineating its influence on human society, we can say that the truth exists somewhere between fantastic worship and ignorant dismissal. First of all, we know that this some 1,600-page manuscript was composed in the early 19th century by the naturalist, or “supernaturalist,” Erasmus Karl, and details the existence of a species of bird-human that inhabits an archipelago called the Beak-born Islands. A number of its pages include baroque maps of the islands in question, along with illustrations of alien flora and fauna and, most importantly and prominently, the winged beings themselves.

This year marks the 150th anniversary since the first bottle, containing a page of Karl’s manuscript, was discovered, specifically between the pincers of a bleached crab on the coast of Budva, Montenegro. This, the method in which Karl “published” the manuscript, has only added to the idiosyncrasy that has either converted or disgusted relevant experts. Each and every page was rolled into its own bottle and cast into the sea. During the intervening century and a half, around a dozen bottles washed ashore on all countries with a seaside (their contents now published en masse for the first time). The bottles were molded with aid of fire from a translucent shell later identified in the manuscript as a “Clay Conch, a most copious & convenient Resource of Nature.” Ascertaining the location of the archipelago based on the appearance of the bottles has proved to be impossible, and the results obtained by oceanographers inexplicably suggest that the islands are capable of nautical mobility, like a flock, perhaps with occasional murmurations. Because bottled pages are still being discovered almost every month, the nidificant manuscript is most definitely incomplete, its prospective length up for debate. Some have purported that an infinite number of bottles will find their way to land, that they will continue to do so far after human civilization is but dust.

~

The Wind Calleth: A Brief Biography of Erasmus Karl

Before I begin my exploration of the manuscript and its influence on human society, I find it necessary to relate what is known of Erasmus Karl’s life. Born in the Netherlands circa 1770, his mother was appalled at newborn baby Karl’s full head of white feathery hair, his thin, elongated body, and the downy web between his taloned fingertips. She blamed the sins of the unknown father, while others whispered that Karl’s appearance was the byproduct of a professionally prurient mother. Regardless of their origin, the unfortunate mutations condemned Karl as an outcast, something to be shooed, ogled, or at best tolerated. It wasn’t long until young Karl despised his reflection, taking extreme measures to change it, as is written in his unpublished journals. First he shorn his hair, which highlighted his teardrop-shaped skull, then he filed his fingernails, sometimes with such desperation that he exposed and bloodied the nail beds, and finally he searched for a type of glove that could hide the finger webbings. Deeming the search futile, he excised the vein-thin skin as if it were the film on a Dutch custard. He bled profusely the first time, but afterward it was merely a matter of maintaining the V-shaped scabs.

Aside from his repelling physical characteristics, Karl was a relatively normal and healthy young boy, until, later in school, he became obsessed with nests, spurred by one he had witnessed being constructed outside his bedroom window. He was amazed to see it built with not just twigs and leaves, but clothespins, apple slices, strands of a stranger’s hair, the string from a cup-and-ball, and other miscellaneous objects. The peculiarity of it inspired him to craft his own nests, which he planted, waiting for random birds to make them home. Impatient, he began to track down authentic nests in trees and the nooks of buildings and replace them with his synthetic ones. Some of his nests resembled the real thing, while others were of odd shapes, pyramids and Klein bottles, or made from strange materials, such as quasicrystals and gaseous gelatins. He was compelled to record the birds’ reactions to their new homes. Some of them simply moved elsewhere, while others were driven to infanticide, either eating their younglings or dashing their unhatched shells against rocks. He was further horrified to discover that sphere-shaped nests of chlorophyll caused the birds’ wings to deteriorate into stubs but was later pleased to determine that alabaster dodecahedrons produced birds with wingspans up to five feet. Other nests also seemed to have a positive effect, causing the inhabitants to sing more beautifully, to love their chirping chicks more so than ever before.

It wasn’t long until young Karl despised his reflection, taking extreme measures to change it, as is written in his unpublished journals.

To read the rest of this story, check out the Mad Scientist Journal: Autumn 2019 collection.

Luisa Sontag holds multiple PhDs from a variety of universities. Her wide range of knowledge is reflected in her published work. For example, her essay on time’s golden spiral shape was published in Quark, her research on the gene-popping of rare squids was featured in Subaquatic Studies, and her six-volume history of vanished continents was published by Samurai Books. Up until his death, she was collaborating with Stephen Hawking on a book about theoretical flora and fauna titled A Brief Visit to Neighboring Planets. Dedicated to Hawking, it is scheduled to be published next year.

George Salis is the award-winning author of Sea Above, Sun Below (forthcoming from River Boat Books, 2019). His fiction is featured in The Dark, Black Dandy, Zizzle Literary Magazine, The Sunlight Press, Unreal Magazine, and elsewhere. His criticism has appeared in Isacoustic, Atticus Review, and The Tishman Review, and his science article on the mechanics of natural evil was featured in Skeptic. He is the editor of The Collidescope and is currently working on an encyclopedic novel titled Morphological Echoes. He has taught in Bulgaria, China, and Poland. Find him on Facebook, Goodreads, and at www.GeorgeSalis.com.

Leigh’s professional title is “illustrator,” but that’s just a nice word for “monster-maker,” in this case. More information about them can be found at http://leighlegler.carbonmade.com/.

“In Communion with the Invisible Flock: Erasmus Karl and the Nidificant Manuscript” is © 2019 George Salis

Art accompanying story is © 2019 Leigh Legler