An essay by Barnetby Richards, as provided by Paul Williams

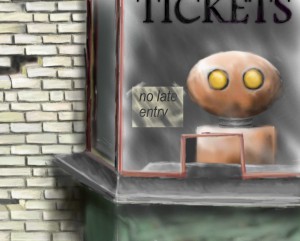

Illustration by Justine McGreevy

The author recognises that a scientific journal is not the place to mention personal information, but is grateful for the editor’s indulgence, and trusts that the reader will understand the significance.

14 April 2020 was the day that I saw the world drown and the day when I was reunited with my son.

We met outside the only surviving cinema in New York. Nineteen screens reduced to six in less than a decade. Five of the films being shown could be hired from the DVD shop over the road for a fraction of the price. The sixth, which everyone was queuing for, was officially labelled Time Recorder 512. The nickname on the streets and on the blog-sites was Deluge.

None of the previous 511 Time Recorders, not even the first, had generated such publicity. It was a return to the days of big, eagerly anticipated Hollywood blockbusters, with the difference being that this popularity was dictated solely by the prospective audience rather than a corporation’s marketing budget. Even so, I would not normally have bothered watching, but Aidan expressed an interest and my presence in the American States gave us an opportunity to meet. The cinema is still recommended as a sensible place for a first date when you don’t yet know how to talk to your new prospective partner. I took Aidan’s mother to one, shortly after she responded to my repeated requests for more contact. Aidan and I had lots to talk about but neither of us really wanted to confront the past.

I recognised him from his internet photo. He stood outside a poster that showed one of the original Time Recorders, or rods of Baghdad, as they were then called. My colleague, John Chrisholm, had cashed in on the rods with a documentary that charted their history, or the parts of it that we knew about. There was thirty minutes before the movie began so I talked through the highlights of the documentary, not yet available in the American States due to a delayed copyright deal, with Aidan. It was easier than talking about the divorce, the women, and the decade of no contact. A decade in which I had tried to forget his existence, believing that it was the only option.

I explained that the rods of Baghdad were first sighted over that historic city during the war in the early years of this century. We do not know how long this airborne life form had existed, beyond the perception of humanity, until advanced infrared cameras began scanning the skies above Iraq. They detected several of these minute organisms, noting them for the attention of cryptozoologists, whilst concentrating on the search for human enemies and weapons.

Initially it was thought that the rods were insects, to join the sixteen thousand other new species reported each year. In depth examination revealed that this was not the case, as they do not have any recognisable insectoid features. They are sentient creatures, functioning as organic cameras, created by nature or a deity depending on your particular sensitivity. They capture images within their bodies, storing them on a gelatine-like belt that seems to serve no other purpose. It is possible to retrieve the images by dousing the time recorder in a chemical concoction that destroys the host but allows the film to first be converted so it can be shown to people. I had to explain the concept of traditional film photography to Aidan and was pleased that he showed a genuine interest in science.

The New York cinema, like all others, had declared that no late entrants would be admitted and, so I was told by the obliging robot at the entrance, had increased their usual prices. The advance booking had cost fifty dollars each, although I paid for Aidan, plus a three percent booking fee.

To read the rest of this story, check out the Mad Scientist Journal: Summer 2012 collection.

Barnetby Richards is Professor of Forensic Pathology at London Hospital. He was born in Dallas and educated at the New York State University. His television series, CSI Reality, ran for two series and was shortlisted for Best Science Program. He is the author of two acclaimed textbooks and is frequently called upon as an expert witness in legal cases.

Paul Williams is a writer best known for his study of the wolf in England, Howls of Imagination, published by Heart of Albion in 2007. He also wrote The Mystery Animals of Great Britain: Gloucestershire and Worcestershire and has contributed articles to magazines such as BBC History and Ripperologist. 44 of his short stories have been published, including the following contributions to anthologies, “To Kill a Nandi Bear” in Doctor Who Short Trips Past Tense, and “Song Ji and the Wolf” in The Blackness Within.

Justine McGreevy is a slowly recovering perfectionist, writer, and artist. She creates realities to make our own seem slightly less terrifying. Her work can be viewed at http://www.behance.net/Fickle_Muse and you can follow her on Twitter @Fickle_Muse.

Follow us online: